How LinkedIn Built a Pipeline That Scales to 230M Records/sec Without Breaking SLAs

From partition strategy to adaptive throttling, the playbook behind Venice’s ingestion evolution.

Fellow Data Tinkerers

Today we will look at how LinkedIn ingests data at scale.

But before that, I wanted to share with you what you could unlock if you share Data Tinkerer with just 1 more person.

There are 100+ resources to learn all things data (science, engineering, analysis). It includes videos, courses, projects and can be filtered by tech stack (Python, SQL, Spark and etc), skill level (Beginner, Intermediate and so on) provider name or free/paid. So if you know other people who like staying up to date on all things data, please share Data Tinkerer with them!

Now, with that out of the way, let’s get to Venice: LinkedIn’s data storage platform

TL;DR

Situation

Venice powers LinkedIn’s AI-driven products and has scaled to 2,600+ stores with workloads spanning bulk loads, streaming updates and active/active replication. The ingestion pipeline had to handle throughput-heavy, CPU-heavy and latency-sensitive traffic under eventual consistency.

Task

Redesign ingestion to scale to 230M writes/sec while preserving ordering and protecting read and write SLAs. Support hybrid stores, partial updates and multi–data center replication without destabilizing clusters.

Action

Scaled bulk ingestion with partition tuning, shared consumer/writer pools and direct SST writes; tuned RocksDB via compaction triggers and BlobDB to manage amplification. Optimized CPU-heavy paths using Fast-Avro and parallel processing, then enforced priority pools and adaptive throttling to protect current-version latency.

Result

Venice now handles 175M+ key lookups/sec and 230M+ writes/sec in production. It maintains a write latency SLA under 10 minutes while safeguarding read latency as the top priority.

Use Cases

Large-scale feature stores, real-time recommendation systems, hybrid data serving, low-latency notification

Tech Stack/Framework

Apache Spark, Apache Samza, Apache Kafka, RocksDB, Fast-Avro, Adaptive Throttling

Explained further

Background

Venice is an open-source derived data storage platform and LinkedIn’s default storage layer for online AI use cases. It sits behind products like People You May Know, feed, videos, ads, notifications, the A/B testing platform, LinkedIn Learning and more.

Since Venice launched internally in 2016 it has scaled from a handful of stores to over 2,600 production stores. The workloads also evolved a lot. It started with “just bulk load a dataset” and grew into a mix of:

Bulk loading huge offline datasets

Nearline streaming updates

Active/active replication across data centers

Partial updates that merge fields and collections

Deterministic write latency expectations under eventual consistency

This post walks through how the ingestion pipeline was revamped to hit 230 million records per second in production, what changed across the architecture, which optimizations moved the needle and how different workload types get tuned. A lot of these ideas are portable if you run any distributed ingestion system where ordering, throughput and predictable latency all matter at once.

Venice overall ingestion pipeline

At a high level, store owners write to Venice through three paths:

Bulk loads from an offline processing platform (example: Spark)

Nearline writes from a streaming processing platform (example: Samza)

Direct writes from online applications

No matter which path you take, the writes all pass through an intermediate PubSub broker layer. From there, the Venice Storage Node (VSN) consumes messages and persists data locally using RocksDB (an embedded key-value store).

The pipeline sounds straightforward until you operate it at scale. The same ingestion path has to support very different workloads. Some are throughput-driven (bootstrapping a massive store). Some are latency-driven (current-version updates). Some are CPU-heavy (partial updates and conflict resolution). Some are I/O-heavy (compaction, SST churn).

The following sections will look at the challenges and how the LinkedIn team resolved them.

Use case 1: bootstrapping from offline dataset

Venice users can run bulk load jobs using offline processing platforms such as Spark to push new data versions to Venice stores. The hard part is performance for large or massive stores. If you want to find bottlenecks you need to understand the ingestion path end to end.

What happens during a bulk load

A Venice Push Job (VPJ) creates a new version topic for the new store version, split into multiple partitions

The Spark job uses a map-reduce framework to produce messages to that version topic

It keeps one reducer per topic partition so message ordering is preserved

On the other side, the VSN spins up consumers, reads messages and persists them into RocksDB

There is one RocksDB instance per topic partition

So you can hit bottlenecks in three obvious places:

producing

consuming

persisting

Production experience says you will hit all three, just not on the same day.

Improving producing and consuming throughput

The usual first lever is increasing the number of partitions for large stores so you can use more of the PubSub cluster capacity. More partitions tends to mean more parallelism and more throughput.

But it comes with trade-offs:

more partitions means more management overhead across Venice and PubSub

there is a throughput ceiling per PubSub broker

So partition count is not a free lunch. It’s a knob that buys you throughput and charges you complexity.

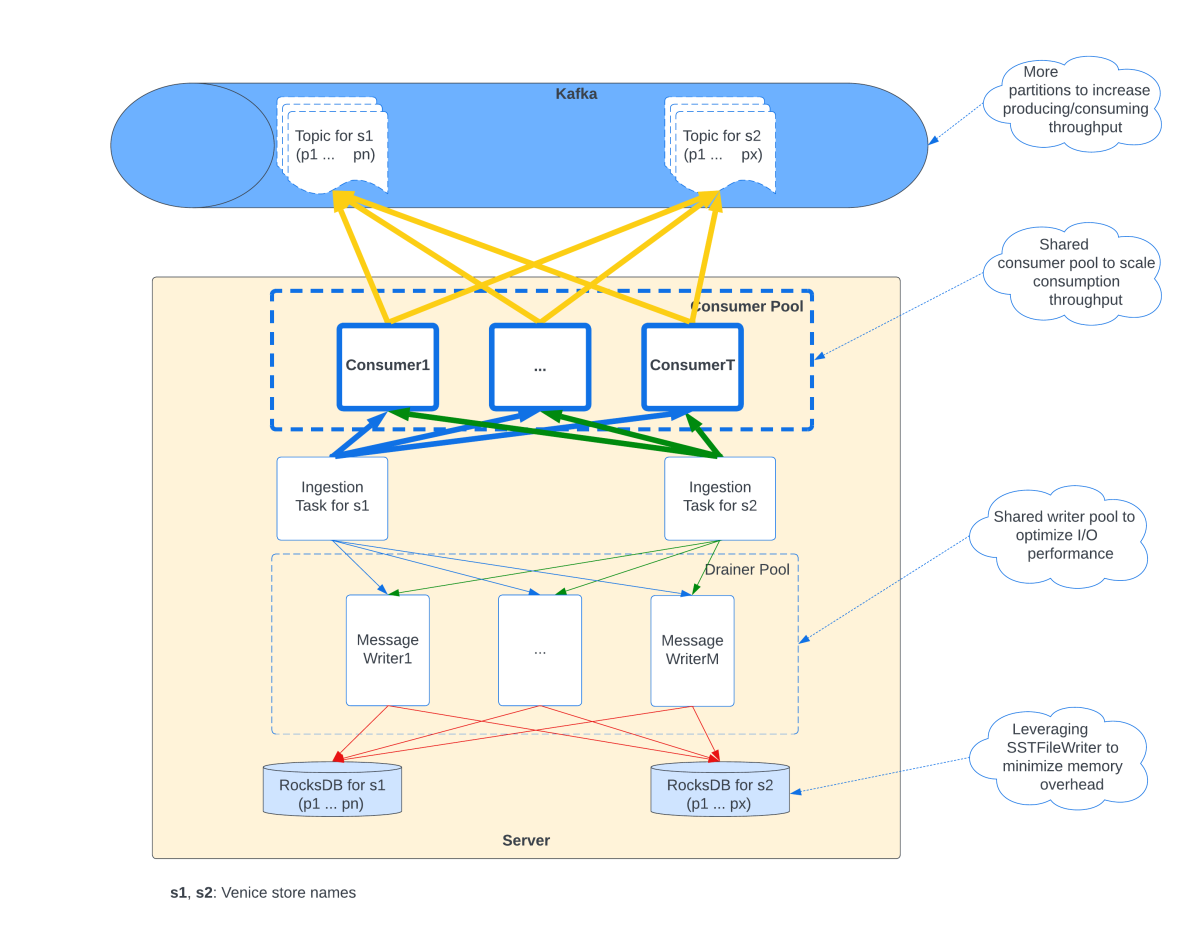

Enhancing consumption scalability

To keep up with production, VSN uses shared consumer pools across all hosted stores.

Instead of “one store version, one set of consumers,” each store version can use multiple consumers by distributing hosted partitions among them. The point is to keep multiple connections per PubSub broker to speed up consumption (similar to a Download Manager).

The pool approach also does something boring but important: it sets an upper limit on total consumers which puts a ceiling on cost.

Optimizing I/O performance

VSN uses a shared writer pool to persist changes concurrently across multiple RocksDB instances and use local SSD capacity effectively.

Ordering is critical in Venice so for any given RocksDB instance there is only one writer actively writing to it. You still get concurrency across instances, not inside one instance which is the compromise that keeps ordering intact.

Minimizing memory overhead

Because messages for a partition are strictly ordered (thanks to the map-reduce framework), Venice uses RocksDB’s SSTFileWriter to generate SST files directly. That significantly reduces memory overhead during ingestion.

Ingestion workflow in Venice Server

Put together, the optimized workflow is basically: use the PubSub layer for distribution, use consumer pools for scalable reads, use writer pools for SSD throughput, preserve ordering by design and avoid memory blowups by writing SST files directly.

Use case 2: hybrid store

Venice supports Lambda architecture style use cases by merging updates from both bulk loads and nearline writes. Users query a single store and get a unified view.

Venice hybrid store workflow

How it works:

each bulk load creates a new store version

that version has a new Kafka topic and a new database instance

real-time updates produced by a Samza job via a real-time topic are appended to both version topics to keep them current

once the new version catches up fully, it is swapped in as the active version to serve reads

The hybrid store is important because it gives you a clean “new version build” story without losing real-time freshness. But it creates a new challenge: the database transitions from read-only to read-write.

That’s where RocksDB tuning matters, because duplicates start showing up more often. Keys get updated or deleted after they were inserted. RocksDB uses log compaction to remove stale entries, but that compaction has overhead: scan, merge, rewrite SST files, consume CPU, I/O and disk.

So the core problem becomes: tune RocksDB so you can balance three competing types of pain.

Write amplification: bytes written to storage vs bytes written to the DB

Read amplification: number of disk reads per query

Space amplification: size of DB files on disk vs the actual data size

Venice uses leveled compaction by default and relies primarily on two methods to balance those trade-offs.

1. Tuning the compaction trigger

The key setting here is:

level0_file_num_compaction_trigger

This controls the max number of files allowed in Level-0. Once you exceed it, compaction kicks in to push SST files from Level-0 to Level-1 and onward as upper levels fill.

Why it matters:

higher threshold → fewer compactions → lower write amplification

but also more Level-0 files → higher read amplification since reads may need to scan multiple files

plus higher space amplification because duplicates hang around longer

Venice tunes this per cluster because clusters have different bottlenecks:

memory-serving clusters want data in RAM to speed up lookups. Memory is the limiting resource, so they set a lower threshold to reduce space amplification

disk-serving clusters are often limited by disk I/O, so they set a higher threshold to reduce compaction frequency and lower disk write rate

This is a practical tuning philosophy: tune to your real bottleneck, not a generic best practice.

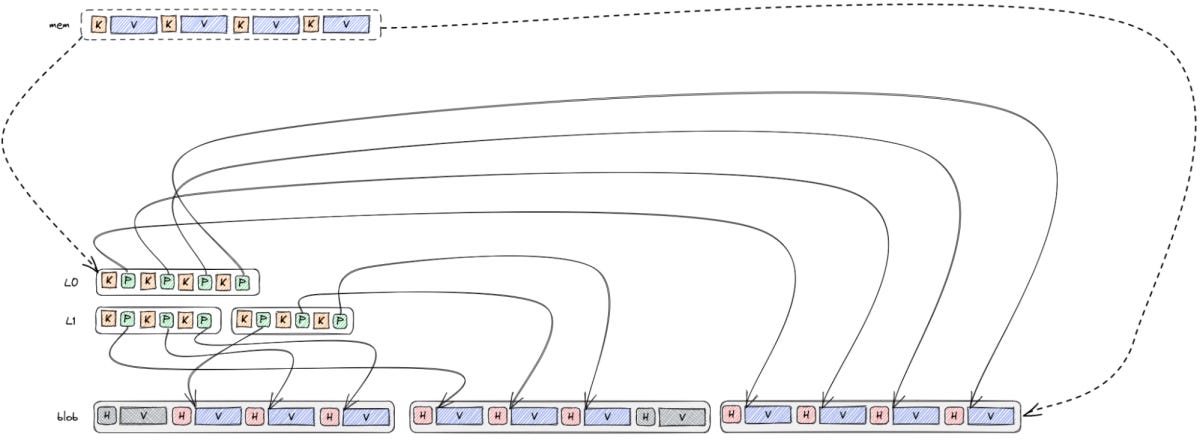

2. RocksDB BlobDB integration

BlobDB is aimed at large-value workloads through key-value separation:

Large values go into blob files

LSM tree stores small pointers

This avoids copying large values repeatedly during compaction, reducing write amplification. The cost is additional space amplification because blobs can become unreferenced and require garbage collection.

For Venice, BlobDB integration reduced write amplification significantly in multi-tenant clusters, especially for large-value use cases. The reported impact here is big: more than a 50% reduction of disk write throughput. That matters because it avoided scaling out clusters when CPU and storage space were still available.

The win here is: you stop paying the compaction tax over and over on the same large payloads.

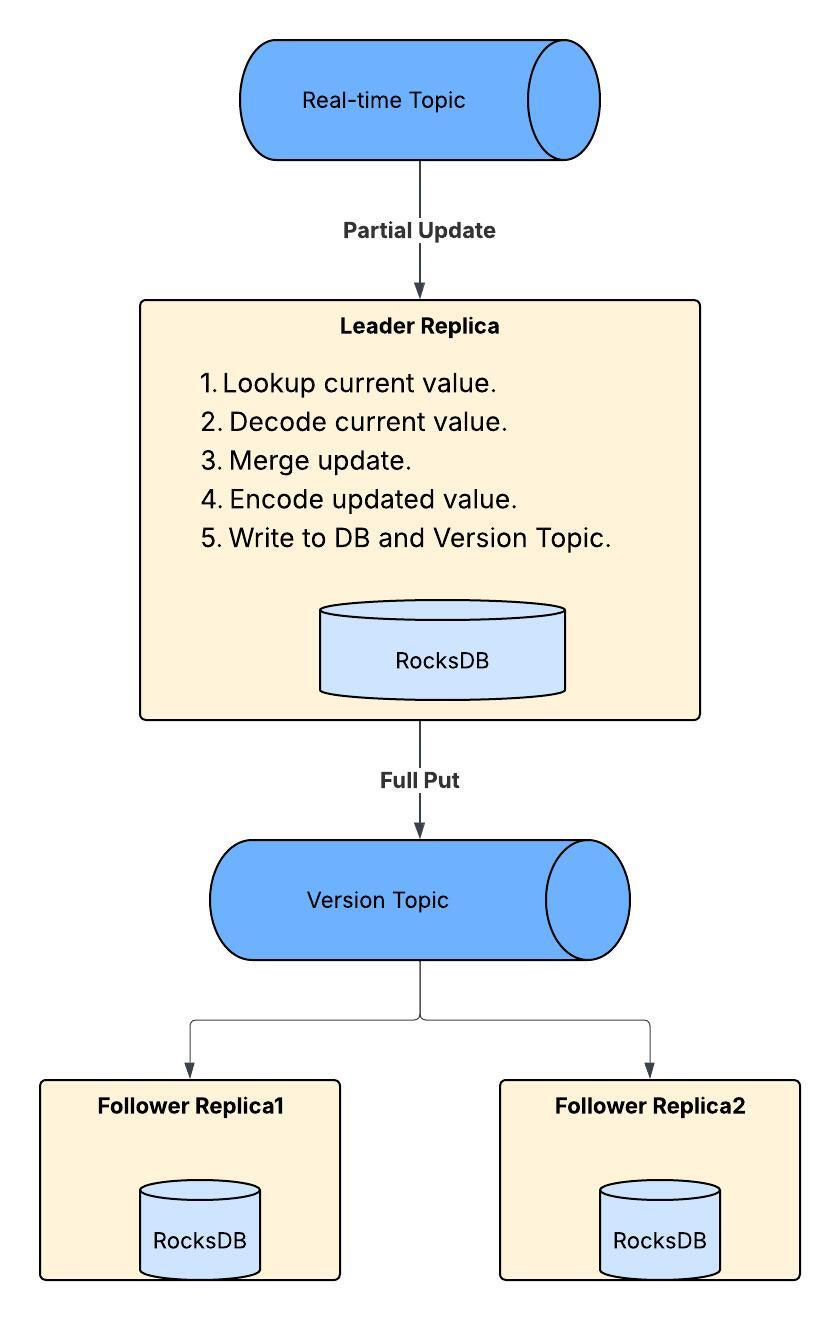

Use case 3: Active/active replication with partial update

Venice guarantees eventual consistency, not strong consistency. That matters because it means you cannot just do read-modify-write operations directly due to write delays.

To handle this, Venice introduces partial update, a specialized operation that supports field-level updates and collection merges.

Venice partial update workflow

Inside the Venice server, the leader replica:

decodes the incoming payload

applies the update

re-encodes the result

writes to the local database

writes to the Version Topic

follower replicas consume the merged results

Most of that is CPU-heavy.

Then the platform evolved further with active/active replication across multiple data centers. The key mechanism is deterministic conflict resolution (DCR), similar to CRDTs. Venice tracks update timestamps at row and field levels, compares incoming timestamps with existing ones and decides to apply or skip.

Venice Active/Active workflow

Now the leader replica has even more to do for DCR:

timestamp metadata lookup

decoding

encoding

Again: CPU heavy. So the optimisation below focus on CPU efficiency.

1. Fast-Avro adoption

Fast-Avro was originally developed by RTBHouse but LinkedIn took over maintenance under the LinkedIn namespace and introduced many optimizations.

The key idea: Fast-Avro is an alternative to Apache Avro serialization and deserialization using runtime code generation which performs significantly better than the native implementation. It supports multiple Avro versions at runtime and is widely adopted inside LinkedIn.

Venice fully integrated Fast-Avro and saw, in one major use case, up to a 90% improvement in deserialization latency at p99 on the application side.

2. Parallel processing

In the traditional pipeline, DCR and partial update operations were executed sequentially, record by record within the same partition. That leads to CPU underutilization.

Venice introduced parallel processing so multiple records can be handled concurrently within the same partition before producing them to the version topic, while still preserving strict ordering in the final step.

Result: significantly improved write throughput for these complex record types.

Use Case 4: Active/active replication with deterministic write latency

Eventually consistent systems still get judged by human expectations. People want their writes to show up and they want it to happen predictably.

Venice is versioned and can ingest backup, current and future versions concurrently in a single server instance. In practice though, only the current version serves reads so deterministic write latency guarantees focus mostly there.

To improve determinism, Venice introduced a pooling strategy in ingestion with different priorities for different workload types. The Venice consumer phase is the first phase in the server ingestion pipeline and controlling the polling rate via pools is how prioritization happens.

Broad priority tiers:

top priority: active/active and partial update workloads for the current version on the leader replica (CPU-intensive and latency-sensitive)

next: other workload types targeting the current version

then: active/active or partial update workloads for backup or future versions on the leader replica

finally: everything else in a lower-priority bucket

This design is trying to do a few practical things:

isolate CPU-heavy workloads so they don’t slow down lighter ones

prioritize the current version so the most up-to-date data flows smoothly

keep the number of pools limited to avoid resource management turning into a second job

The catch is tuning. Clusters see different workloads, store behavior varies widely even within one cluster, throughput swings over time and read traffic changes throughout the day. Static configs force you to tune for worst-case, which wastes resources most of the time.

So Venice introduced adaptive throttling: dynamically adjust ingestion based on recent performance.

if the system is within agreed SLAs, ingestion rates are adjusted according to priorities

if an SLA is violated, ingestion is throttled back immediately

Defining the SLAs matters. Venice focuses on two key criteria:

Read latency SLA: highest priority. Never violate read latency SLAs, even if it costs ingestion throughput

Write latency SLA for the current version: while read latency SLAs are met, write latency for the current version becomes top priority, pools are tuned proportionally to maximize utilization and throughput

Wrapping up

With these optimizations, Venice at LinkedIn handles:

Over 175 million key lookups per second

Over 230 million writes per second

While maintaining a write latency SLA under 10 minutes

The full scoop

To learn more about this, check LinkedIn's Engineering Blog post on this topic

If you are already subscribed and enjoyed the article, please give it a like and/or share it others, really appreciate it 🙏