How to Build a Recommendation System at Scale: Insights from Instacart

A Senior ML Engineer's perspective on production constraints, rules vs ML and the workflow behind large-scale recommender systems

Fellow Data Tinkerers,

Following on from previous posts talking to people in the field, today I will be talking with Ahsaas Bajaj who is a Senior Machine Learning Engineer at Instacart. He works on large-scale recommendation systems that serves millions of customers.

We talked about his rise from software engineering to machine learning at Instacart, how does he decide between rules based vs ML approaches and how he approaches the work now as a more senior stakeholder.

So without further ado, let’s get into it!

Can you tell us a bit about your role?

I’m a Senior ML Engineer at Instacart, working across customer and shopper experiences on large-scale recommendation systems that make millions of decisions each day. For the past three years, I’ve led the technical strategy for the Product Substitutions ML system, focused on solving the out-of-stock problem.

The goal is simple: when an item isn’t available, suggest a replacement that preserves customer intent and keeps the order intact. My role spans system design, modeling and evaluation, balancing customer satisfaction, shopper efficiency and business impact at scale.

How did you get into machine learning?

My path into ML wasn’t a straight line. I started as a software engineer at Samsung Research on the on-device search team, which pushed me deep into information retrieval and search system design. That work sparked an interest in research and led me to pursue a graduate degree in computer science.

It shaped how I approach ML today: less focus on models in isolation, more on how systems behave in production. I wanted that work to have real user impact, which took me to Walmart Labs and eventually to Instacart.

Ahsaas’s path

software engineer → data scientist → ML engineer → senior ML engineer

What does a ‘typical’ week look like for you?

As I’ve moved into a more senior role, the balance has shifted from pure coding to a mix of execution and direction. My week usually breaks down into three buckets:

Alignment (30%): The glue work. I spend time with product, backend engineering, and leadership aligning on roadmaps. The focus isn’t just what we’re building, but why, making sure ML work ties directly to business goals.

Deep work (30%): Hands-on modeling, coding and system design. Staying close to the code is non-negotiable for me, even at a senior level.

Analysis and “the why” (40%): This is where I spend the most time. I dig into model errors, read raw customer complaints about failed substitutions and sanity-check improvement ideas. This is also where I write proposal docs. In my view, the highest-leverage work a senior MLE does is deciding what problems to solve next, not just executing on what’s assigned.

How do you decide when a problem actually needs ML or if rules-based is good enough?

I think about it in terms of complexity versus value.

If a problem can be solved deterministically with clear rules and those rules are stable and understandable, that’s often the right solution. Machine learning becomes useful when the space of behaviors is too large, nuanced, or context-dependent for rules to scale.

Good data is also a prerequisite. Without reliable signals and feedback loops, even the most sophisticated model won’t perform well in production.

You have written about your work on a recommendation model at Instacart. Can you share a summary of what you have done?

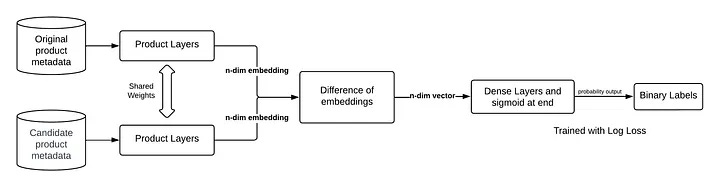

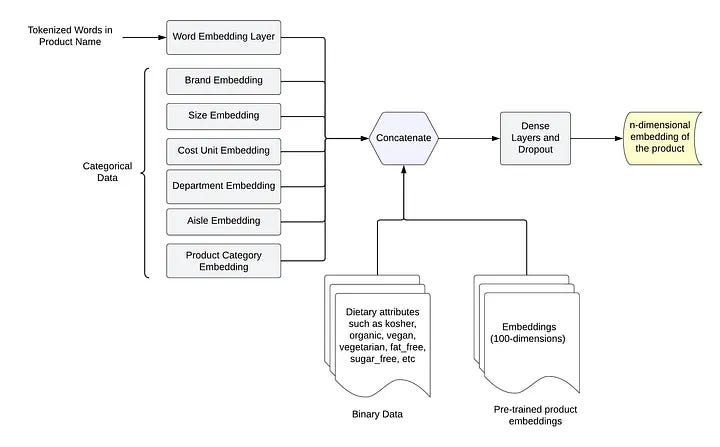

I’ve spent the past three years leading the technical development of Instacart’s Product Substitutions system, which handles millions of replacement decisions daily. The core challenge is deceptively simple: when a customer’s requested item is out of stock, what should we suggest instead?

What makes this interesting from an ML perspective is that it’s fundamentally a relevance problem, not a search problem. We’re not just matching product attributes—we’re trying to understand what the customer actually wanted and find alternatives that preserve that intent. This required rethinking how we model the relationship between items, how we define “good” substitutions, and how we evaluate success in a way that maps to real customer satisfaction.

The system has evolved significantly over time, moving from simpler heuristics to more sophisticated learned representations. But the north star has always been the same: keep orders complete while respecting what customers actually care about.

And what has been the impact on the business?

Substitutions sit at a critical junction in the order lifecycle. When done well, they’re invisible - customers get what they need and the order stays intact. When done poorly, they create friction everywhere: customers reject items or request refunds, shoppers waste time on unsuccessful suggestions, and order values drop.

Our work has meaningfully moved the needle on the metrics that matter: replacement acceptance rates, refund frequency, and what we call “perfect order fill rate”—the percentage of orders where every item was either found or successfully replaced. These improvements compound across millions of weekly orders.

Beyond the immediate transactional metrics, we’ve also seen positive signals in repeat ordering behavior and customer satisfaction scores, particularly for orders that required multiple substitutions. Instacart has referenced this system publicly when discussing operational improvements at scale.

For me, the real validation is when customers don’t notice the algorithm at all - they just notice their groceries arrived complete.

What does the tech stack look like for ML at Instacart?

Instacart’s ML stack is built around an internal platform called Griffin, which standardizes the end-to-end ML lifecycle, from feature engineering and training to deployment and real-time inference. A core piece of this is a shared Feature Marketplace, where teams define, version and reuse batch and streaming features with strong offline-to-online consistency.

Workflows are orchestrated with Apache Airflow and model training runs through a unified abstraction that supports multiple compute backends and common ML frameworks. With Griffin 2.0, the platform moved to a Kubernetes-based setup and added distributed training with Ray, which significantly improved scalability and iteration speed.

Griffin also includes a centralized model registry and metadata store, making experiments easier to track and reproduce. In production, models are deployed as standardized services that handle feature loading and low-latency inference across both customer and shopper experiences.

The main benefit is focus: teams spend less time on infrastructure and more time on modeling, evaluation and trade-offs.

How do you use AI in your day-to-day work and where do you find it genuinely valuable?

I’ve integrated GenAI primarily to shift my focus from execution to decision-making. It’s useful for routine tasks like scaffolding data pipelines or optimizing SQL queries, but I find the highest leverage comes from qualitative analysis.

I routinely feed thousands of customer comments and shopper notes about bad substitutions into LLM-driven pipelines that cluster feedback into coherent themes. What used to be unstructured noise becomes a prioritized list of failure modes. This allows me to spend less time parsing data and more time solving the specific problems that actually impact customer trust.

How has your perspective changed moving to a more senior role?

The biggest shift is realizing that Judgment > Code. Early in my career, I obsessed over the how - the architecture, the libraries, the latency. Now, I obsess over the what and the why. The real work is filtering ideas. In a sea of seemingly good ideas, my job is to find the most bullish one - the one with the highest ROI - and kill the others.

I’ve also learned that Writing is Engineering. You cannot build big things alone. To get buy-in from leadership and cross-functional teams, you must be able to write crisp, narrative-driven proposals that explain why this mathematical solution solves a human problem.

The biggest shift is realizing that Judgment > Code

What’s one thing you wish you’d known earlier about machine learning?

The value of error analysis. It’s easy to celebrate aggregate metrics like accuracy or F1 but the real breakthroughs come from studying the “horror cases,” where the model is confidently wrong. Those examples are uncomfortable to look at but they’re where the most useful ideas come from. You can’t fix what you don’t deeply understand.

If you enjoyed reading this, check out Ahsaas’s original article about his work at Instacart

Was there a question that you would like to ask?

Let me know your thoughts by replying to the email or leaving a comment below!

If you are already subscribed and enjoyed the article, please give it a like and/or share it others, really appreciate it 🙏

The tradeoff between rules and ML is something I run into constantly. What really clicked for me is the emphasis on error analysis rather than aggregate metrics. I spent years chasing F1 scores bfore realizing the "horror cases" teach way more than the 100 times the model gets it kinda right. Also appreciate the honest take on judgement over code at senior levels.