When the Metric Becomes the Monster

A dive into Goodhart’s Law and how smart teams accidentally optimize for the wrong thing.

Fellow Data Tinkerers!

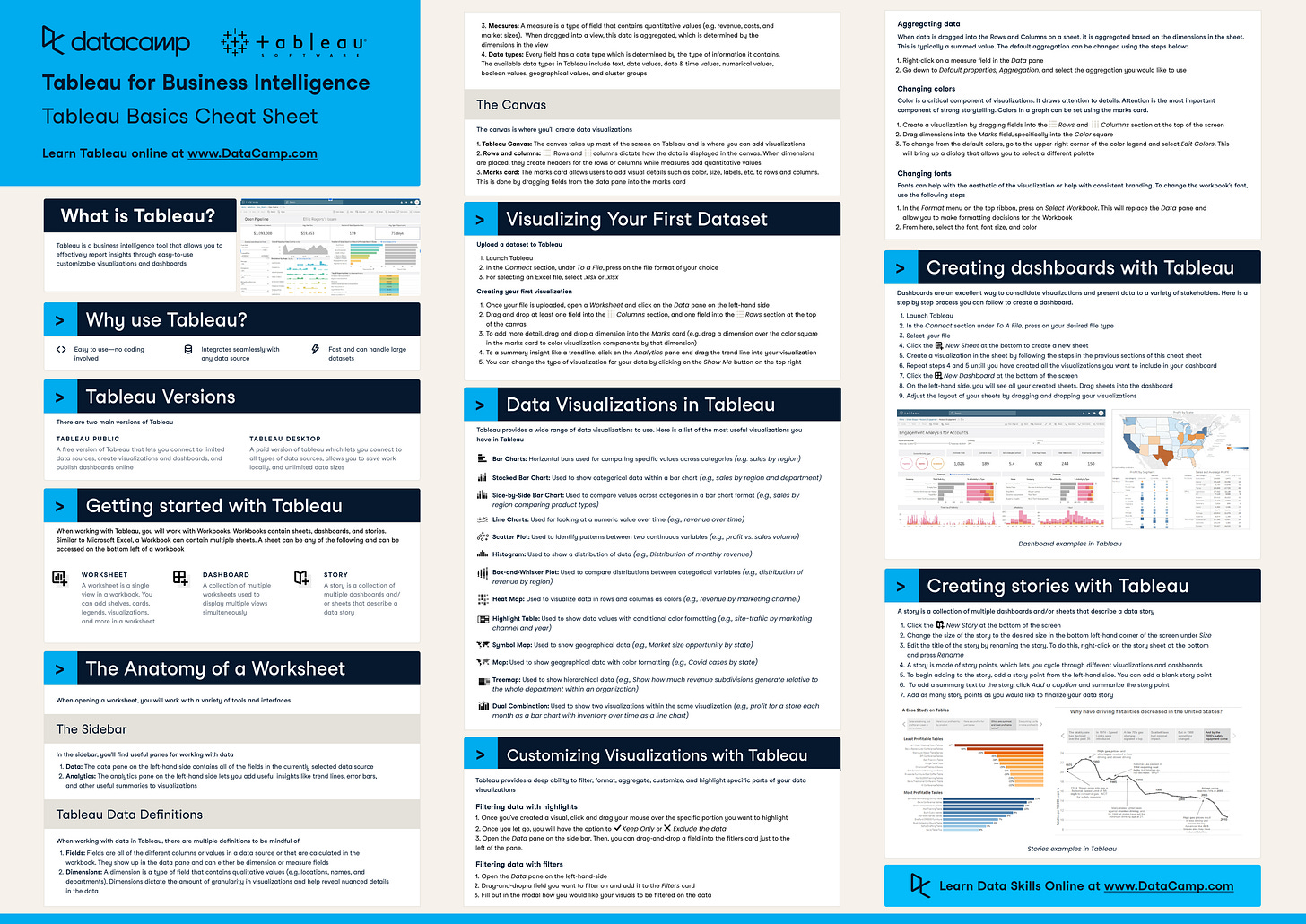

As I mentioned earlier this week, you can have access to 100+ cheat sheets covering everything from Python, SQL, Spark to Power BI, Tableau, Git and many more. You just need to share Data Tinkerer with 2 other people to unlock it

So if you know other people who like staying up to date on all things data, please share Data Tinkerer with them!

Now, without further ado, let’s get into a fallacy you want to avoid!